We examine the same document in two separate folders at the National Archives of Australia (NAA). One copy has parts blacked-out, the other is not redacted. We ask: Were the specific redactions justifiable and what are the broader implications of this inconsistency at NAA?

To redact or not to redact? Questions on access restriction decisions.

A late-1976 four-page report, apparently from church-connected sources, offered a rare independent view on conditions inside Indonesian-military-occupied East Timor. The report, broadly confirming Fretilin-led resistance claims, gained immediate attention from Australian media, NGOs and activists and was analysed for Australian parliamentarians by James Dunn.

The report also came to the attention of the Australian Government at the same time and was assessed by its Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (DFAT) and the Joint Intelligence Organisation (JIO*). More than thirty years later, the relevant folders from DFAT and JIO were released for public access. The JIO copy of the report was significantly redacted before its release in 2011, but the DFAT copy was left completely uncensored (released 2012).

This inconsistency raises doubts on the reliability of NAA decisions on restricting public access to many Timor documents.

What was redacted?

The unredacted DFAT copy shows that the main JIO redactions obscured references to Timorese, Indonesian or international Church organisations. We can reasonably conclude that the redactions sought to either hide or protect the unidentified author’s Church connections.

Was the redaction justified?

In terms of personal safety of the authors, there is no doubt that the redacted material was very sensitive in 1976; other comments in both folders stress this. We strongly doubt, however, that the information was still sensitive in 2011 when this redaction was applied – especially since no individual is immediately identifiable.

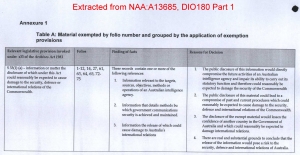

The access decision redacting the report in the JIO folder was specifically based on Section 33(1)(a) of the Archives Act. This provision restricts access to any material which “would damage Australia’s security, defence or international relations”. In a close reading of the reasons for redacting this report (click on graphic above), we cannot see any reasonable basis to invoke Section 33(1)(a) in the case of this document.

Our views are effectively confirmed by the access decision on the DFAT folder. Other material in the DFAT folder was redacted or excluded under Section 33(1)(a), but not this particular document. The DFAT folder also contains additional unredacted material about the original source of the document.

What are the implications?

At the very least we can conclude from this example that NAA restrictions** on access through redaction under Section 33(1)(a) are inconsistently applied. Of more concern is the implication from this particular example that redactions in other NAA documents about Timor may be similarly unjustifiable.

A researcher can wait for up to two years*** for a Timor folder to be examined before being released. As Australian researcher Clinton Fernandes has found, challenging NAA redactions after the initial release of documents can be an onerous process. This is particularly so for materials from intelligence agencies like JIO. It is reasonable, then, for researchers to expect the access decision-making processes to be robust.

Regrettably, this present example certainly throws doubt on the reliability or legitimacy of restrictions on access to some materials at NAA.

———–

NOTES:

*JIO was the name of the Australian military’s intelligence arm, now called the Defence Intelligence Organisation (DIO).

** It is very likely in both cases that the access decisions taken were recommended to NAA by the relevant agencies (ie DIO and DFAT). Nonetheless, it is NAA which takes formal responsibility for the decisions.

*** A CHART analysis of wait-times for NAA access decisions is in preparation.

A very esoteric comment on ABRI weaponry: At paragraph 11 of the “Church-related”-report, the use of “Stalin organs” by ABRI forces is mentioned. This is a reference to the BM-14 Multi-barrelled Rocket Launcher (MBRL – a vehicle-mounted system). BM-14s were noted in December 1975 in counter-battery tasks against Falintil artillery (ie their Rheinmetall-Borsig 75mm Pak.40 howitzers; and Obice 75mm L18 Mod 34 guns). Separately, I have forwarded a photograph of an ABRI BM-14 MBRL at Uatocarabau in October 1985. ABRI PT-76 light amphibious tanks were also in Uatocarabau in October 1985.